I thought I was going to start Comic Envy by posting my opinions about some of the strips I color, mentioning strips and artists. But instead, I am going to drill down to what ties them all together. And that is the method I use.

Currently, I feast on a weekly menu of 20 comic features distributed across three newspaper syndicates. That number is soon to drop to 19 across two syndicates, but that’s for another post. A single daily feature can have from one to four panels. 16 of my features are daily strips, which means coloring up to 64 panels for just those alone.

There’s a popular saying that goes something like this: You want cheap, fast, and good? Pick two! I wish. The job of coloring black and white syndicated comics, which come at you faster than chocolate candies on an “I Love Lucy” conveyor belt, asks for all three. More than anything, it’s a speed game, so shaving seconds off of repetitive tasks really adds up to minutes and hours during a one-week cycle.

If you are familiar with Photoshop, you might be aghast at this image. It’s Photoshop from another century! I won’t insult you with a grade-school simplification of its basic features, but for the rest of you, here’s a quick look at how it works. You have a flat, blank digital canvas before you. The basic toolset that has been around forever gives you a pen, pencil, paintbrush, eraser, paint bucket, airbrush, text tool, and other ways to apply strokes and fills from a palette of millions of colors. Photoshop’s full array of tools and other collapsible palettes looks like an airliner cockpit if they’re all displayed at once. For my purposes, only a few need to be open.

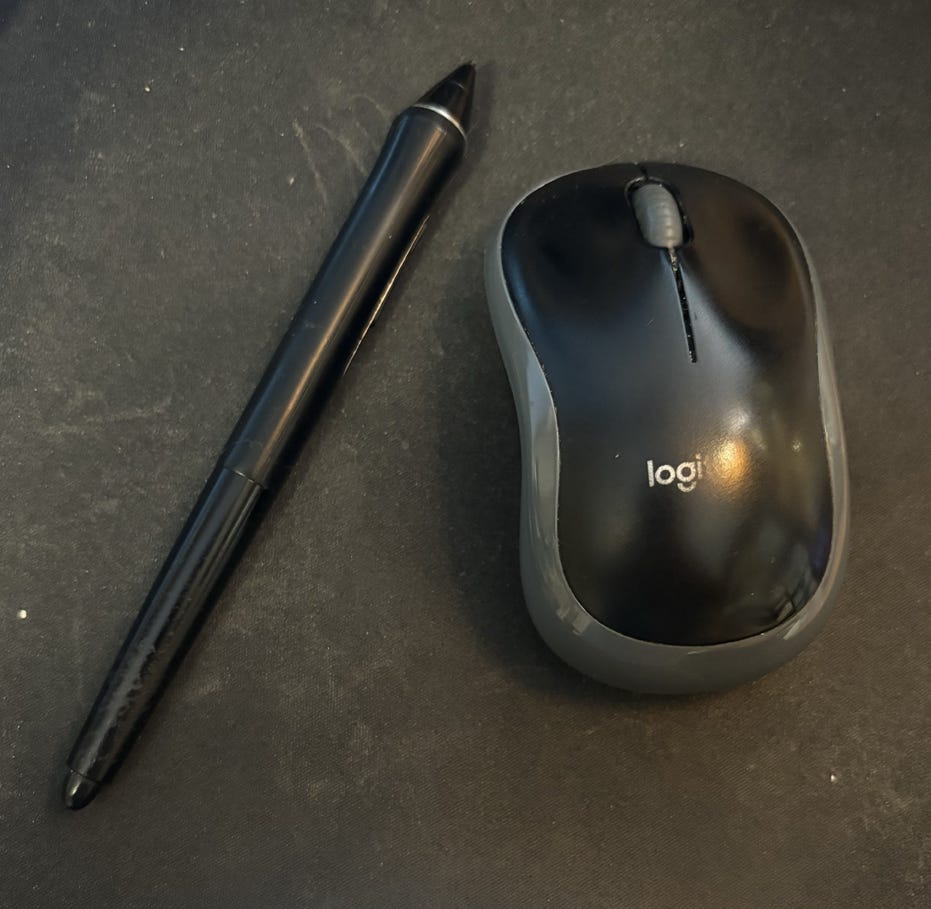

Digital painting tools are applied by a stylus or a mouse or by your fingers if you use a touch-sensitive tablet. Oh, and throw in a keyboard for shortcut options. There’s your compact electronic studio in a nutshell.

At the most rudimentary level, a single layer is all you need for comics. Draw some black shapes and lines, add text, and apply color to the blank areas; maybe leave some areas blank (white). Simple. Easy peasy. Right? Color some comics and hit the golf course by 9 a.m. Well, I don’t play golf, and if I did, my clubs would be collecting cobwebs.

I’ll wrap up this post by thanking you for reading this far. I hope you’ll share my stack with anyone who would like to know from an outside insider what goes on behind the scenes in comic strip production.

I’m looking forward to more behind-the-scenes info on how colors are chosen and applied. Do syndicates specify a standard palette? I ask becasue I’ve always been impressed by what can be achieved by a limited range of colors. For example, the two-color Trucolor process managed to look good in a number of Roy Rogers films.

64 panels! And you have to be sure that every piece of clothing which is interrupted by a different object carries the right color. Yikes.